In a major vote of confidence for Africa’s financial integrity, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has officially removed Nigeria, South Africa, Mozambique, and Burkina Faso from its global “grey list” — a designation reserved for countries with strategic deficiencies in combating money laundering and terrorist financing.

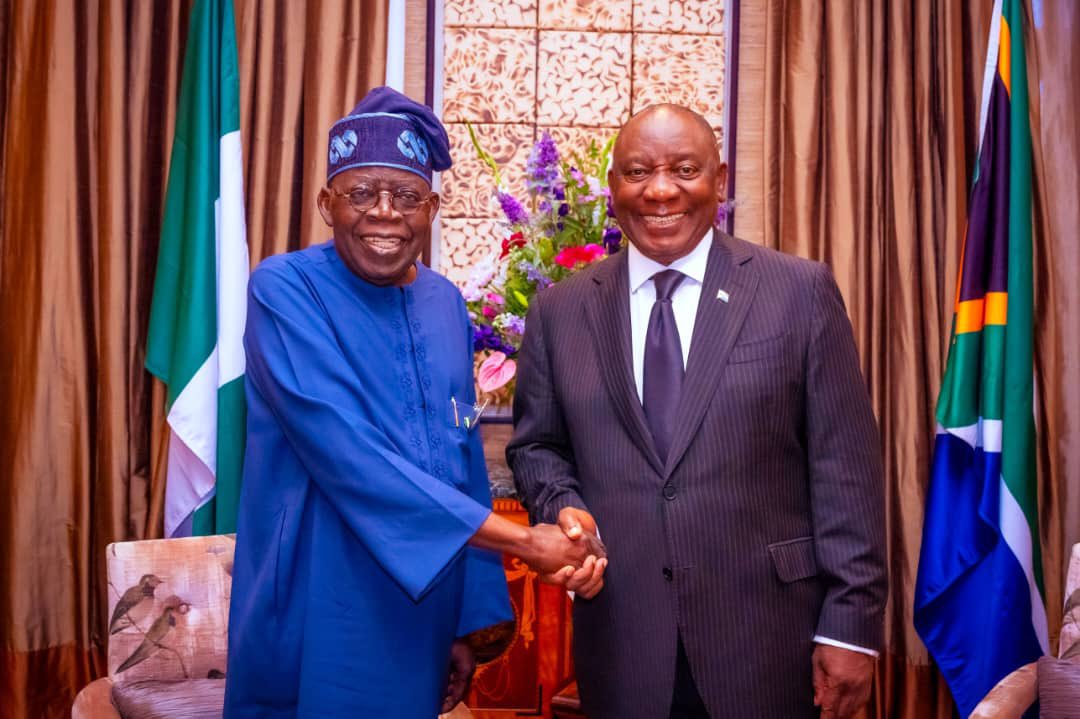

The decision, announced in Paris last Friday, follows years of reform efforts and signals renewed optimism for Africa’s two largest economies, Nigeria and South Africa — both of which have faced economic headwinds and investor skepticism since their inclusion on the list.

The FATF, a global watchdog that monitors how countries tackle illicit financial activities, noted that all four nations had shown “substantial progress and political commitment” in strengthening regulatory systems, improving transparency, and enhancing financial intelligence cooperation.

What the Grey List Means

Countries placed on the FATF’s grey list are seen as having weaknesses in preventing money laundering and terror financing. While not as punitive as the blacklist, the designation often triggers tougher scrutiny from international banks, higher transaction costs, and declining investor confidence. For emerging economies like Nigeria and South Africa — already battling inflation, currency depreciation, and sluggish foreign investment — the grey listing had become a symbol of risk anand instability in the eyes of global financiers.

Reforms That Changed the Game

To secure their removal, the affected nations implemented sweeping reforms. Nigeria tightened its anti-money-laundering laws, increased oversight of digital and mobile money platforms, and strengthened collaboration between its Financial Intelligence Unit and the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC).

South Africa, reeling from years of corruption scandals, introduced legislative changes empowering regulators to track suspicious financial activity and prosecute public officials implicated in illicit dealings.

The FATF lauded these efforts as evidence of “enhanced compliance and institutional resilience,” but warned that sustained vigilance remains essential.

Economic and Social Impact

Experts say the delisting could deliver tangible benefits for citizens and businesses alike. In Nigeria, the move could pave the way for cheaper cross-border transactions, improved access to foreign capital, and gradual stabilization of the Naira as investor confidence returns.

In South Africa, it may translate into lower borrowing costs, job creation, and tighter consumer protection through stronger financial oversight.According to analysts, “This isn’t just about compliance — it’s about restoring trust in African markets and attracting long-term investment.”

Regional Ripple Effects

The FATF’s decision may also have a positive spillover effect on neighboring economies. When Nigeria and South Africa were grey-listed, it cast a shadow of risk over regional markets like Ghana, Kenya, and Côte d’Ivoire. Their delisting now sends a signal that African economies are increasingly capable of self-regulation and global partnership in financial governance.

The Road Ahead

Despite this progress, the FATF has emphasized that monitoring will continue to ensure reforms are sustained. For Nigeria, the challenge lies in maintaining strict compliance amid the rapid expansion of fintech and digital payments.

For South Africa, the focus will be on political accountability and preventing backsliding ahead of its next election cycle.

Ultimately, the delisting marks not just a technical milestone, but a turning point in how the world perceives Africa’s economic systems — as reforming, resilient, and ready for renewed engagement.

What it means for the African Diaspora

For the African diaspora and global Black investors, this development holds deeper meaning.

For years, grey-listing shaped narratives about Africa as financially unstable or systemically corrupt.

But delisting — achieved through reform, collaboration, and accountability — reflects an emerging continental maturity that challenges those stereotypes.

It signals that African nations can meet global standards without surrendering sovereignty, and that governance reform is not just reactive, but self-driven.

For diasporans looking to invest back home — in real estate, startups, or social enterprises — this is a green light. A reassurance that Africa’s financial systems are evolving, its institutions strengthening, and its future markets becoming more trustworthy.